Continuing the series of articles celebrating the lives of Bluebirds who fought for their country. From the football pitch to the battlefield, this is the remarkable story of a Bluebird who kept quiet about his wartime heroics.

Herbert Price Evans, better known as Herbie, was an unsung sportsman who became the first person to play League Football for Cardiff City as well as County Cricket for Glamorgan. Despite his sporting success, it has taken more than century for the story of his immense gallantry on the battlefield to emerge.

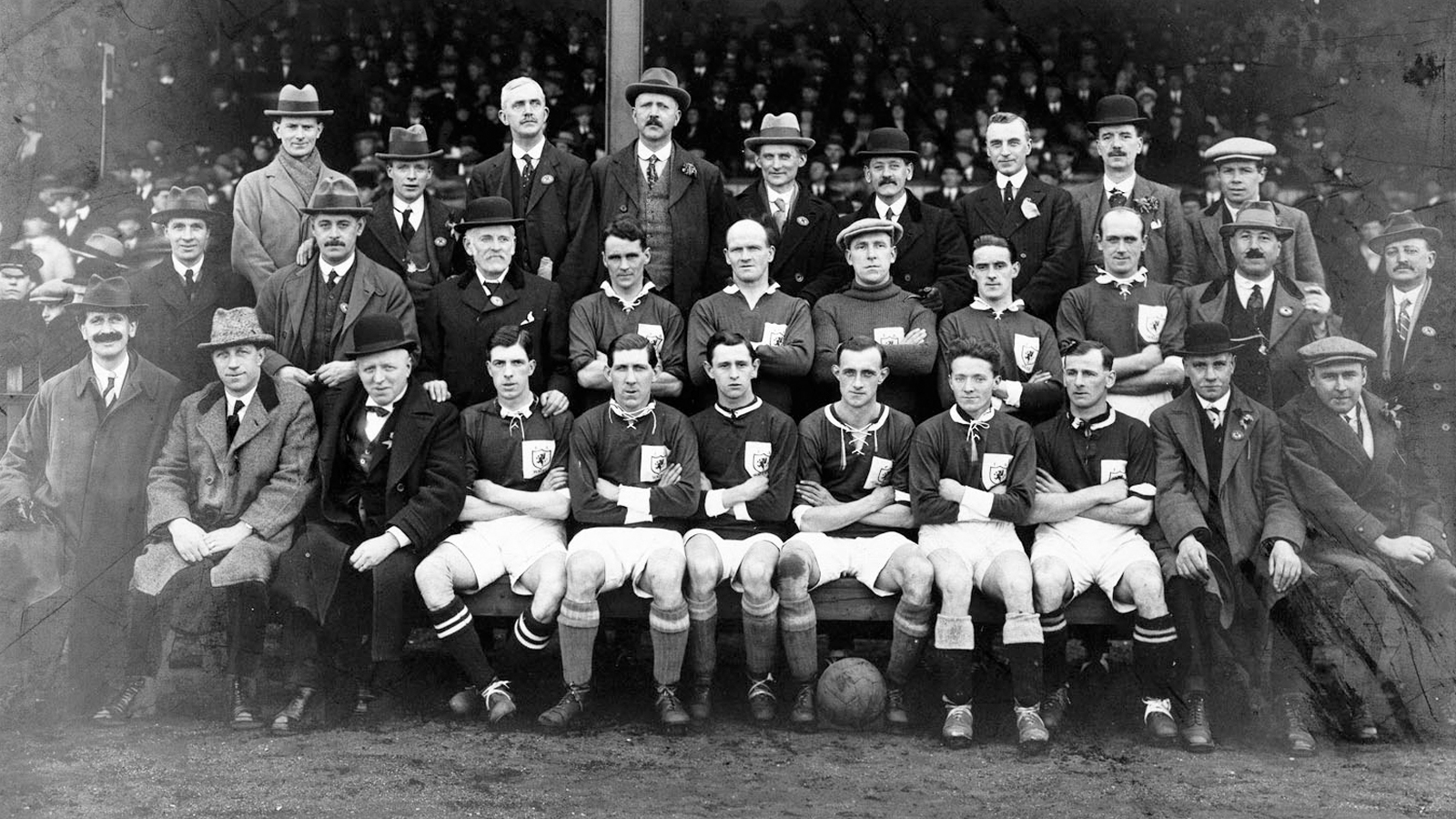

Wales v Ireland at Belfast, 1922. Herbie is pictured in the middle row, fourth from the left.

A Young Sportsman

Herbie was born in Cardiff on August 30th, 1894, and grew up in High Street, Llandaff. At the age of 16 he followed his father Arthur into the clerical profession, and it is thought they worked alongside each other at a local papermill. As a teenager, Herbie developed a reputation as a talented sportsman of great potential: he was a boxer, a cricketer for St. Fagan’s and a Welsh Schoolboy Football International. He soon became a regular in the successful Cardiff Corinthians side that won Welsh Amateur Cup during the 1913/14 season.

His favoured position was originally inside forward, but later in his career he converted to ‘wing half’, a position given to wide midfielders during that time. The term would fall out of use as wide players with defensive roles became more integral to the defence as full backs.

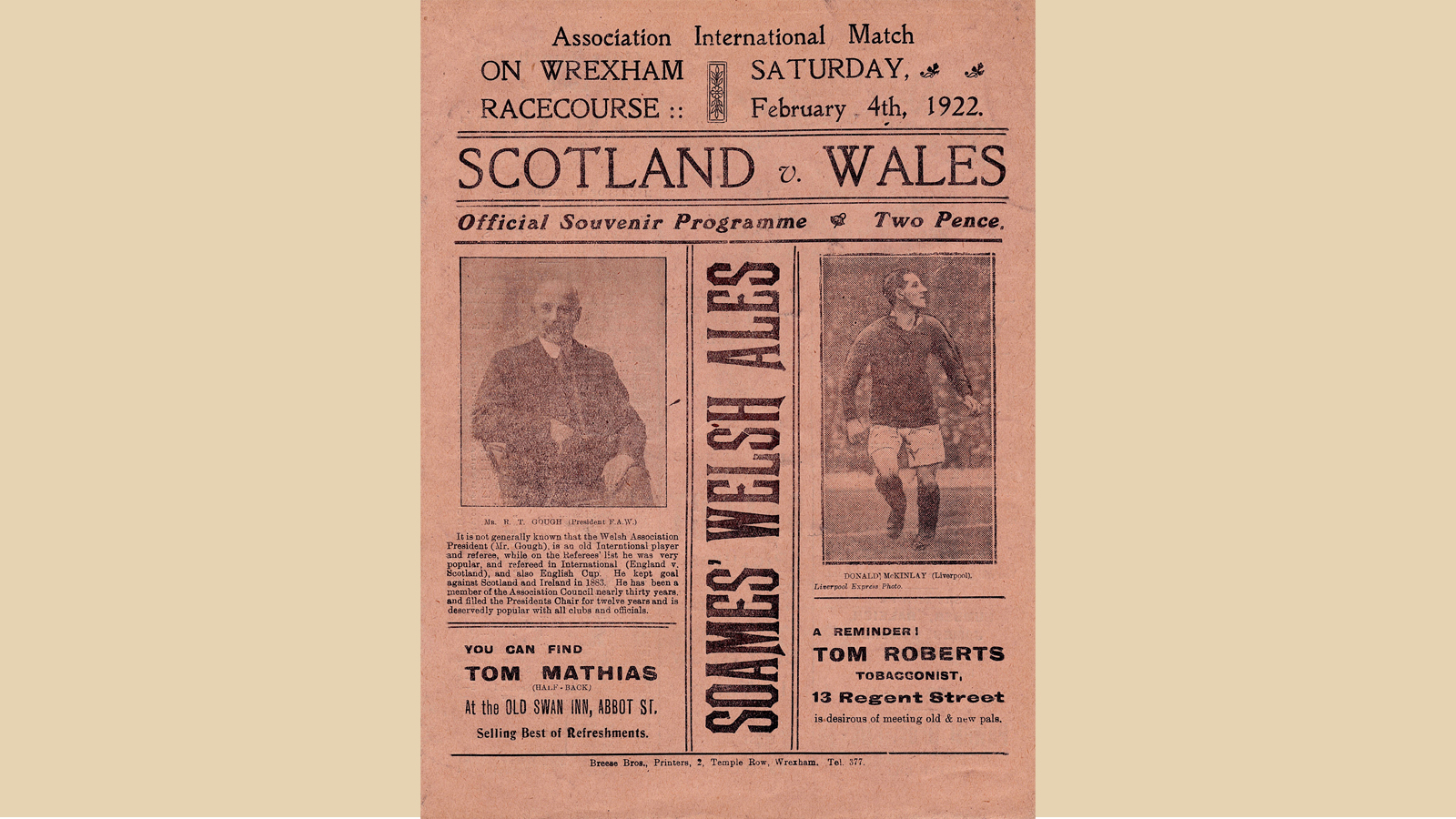

The match programme on the day of Herbie's Wales debut, vs. Scotland at Wrexham, 1922.

In Service

With war clouds looming, Herbie’s football career was put on hold and in September 1914, The Cambrian Daily News reported on his enlistment into the British Army. The departure of Herbie, and a number of his teammates, meant club fixtures were cancelled for the duration of the war.

Herbie joined the Royal Field Artillery and trained as a gunnery soldier during basic training. He qualified as a Driver, which gave him the job of handling the horses that pulled field guns and artillery wagons. The reality is that Herbie steered the reigns of the horses which pulled howitzers across the battlefield.

Sadly, many of the service papers of those who served in the British Army were destroyed during the London Blitz of 1941, and Herbie’s personal army records did not survive. But we do know that following his initial training in the summer of 1915 he was posted to Egypt with the 69th Artillery Brigade where his Division fought against Turkish Forces in Gallipoli before returning to Egypt in early 1916. Herbie then found himself in Mesopotamia, which became known as modern day Iraq, and where he endured the bitter fighting and terrible conditions that marked the campaign to finally defeat the Ottoman Turks.

For the men fighting in Mesopotamia, it meant adjusting to a different type of environment and as one veteran remarked: “[I]t was a horrible climate, now you’ve got more modern conveniences, electricity, and fans and all the rest of it, but we were just in hot sun.” The extreme heat in Mesopotamia (alongside poor medical facilities, lack of clean water, flies, mosquitoes, and vermin) led to appalling levels of sickness and death from disease. Despite the best efforts of medical staff, thousands of soldiers died, especially in the early part of the campaign.

1917 saw the reinforced British and Commonwealth Forces win a series of victories that culminated in the capture of Baghdad, and it was during this campaign that Herbie was decorated for extreme heroism in the face of the enemy. In August 1917, the London Gazette, an official public record, published details of Herbie’s Distinguished Conduct Medal with the following citation:

‘5739 Driver H Evans Royal Field Artillery: For Conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty on three separate occasions. On each he laid a wire behind the infantry under heavy fire thus ensuring co-operation with the Artillery.’

Laying communication wire was an extremely dangerous task as the enemy swept the ground with machine gun and shell fire. It was vital in maintaining fire support from the Artillery for attacking Commonwealth Troops as they approached enemy positions. Herbie had done it three times and survived.

By the end of the war, victory over the Turks in Mesopotamia had cost the lives of 85,000 British and Commonwealth soldiers with another 20,000 dying of disease. Herbie survived and in early 1919 he was discharged from the Army and allowed to return home. He kept a copy of the London Gazette, and it remains with his medal to this day, but unusually there was no mention of the high award in local newspapers either at the time or after the war.

Returning Home & Life As A Bluebird

Like many servicemen and their families, Herbie may have wanted to simply get on with his life back in Wales after a traumatic period of painful loss. Like all soldiers with the same period of service, Herbie would have been entitled to three other medals inscribed with his name rank and service number. These awards were nicknamed Pip, Squeak, and Wilfred after a popular Daily Mirror comic strip of the day, but their current whereabouts are unknown. Formally, the medals were named as the 1914/15 Star, the British War Medal, and the Victory Medal.

After the war, Herbie made a number of appearances for Glamorgan County Cricket Club as a middle-order batsman, but it was his football career that was destined to take off. He was signed by Cardiff City in 1920, joining the club in time to assist the Bluebirds in achieving promotion to the First Division in 1921. Initially he signed as an amateur and remained so long enough to get a Wales amateur cap before going fully professional in 1922.

One reporter described Herbie as: “[D]etermined to succeed: more than a spoiler, he is a constructive half back capable of initiating and joining in combined attacking movements.”

It was fitting that Herbie’s exploits with Cardiff City were recognised with full international honours. He was capped for the first time by Wales against Scotland at Wrexham in 1922 and five more caps followed including one against Ireland in Belfast later in the same year. Herbie’s three subsequent caps came as part of the exceptional Wales team that won the International Championship (or British Home Championship) of 1923/24; Wales saw off Scotland 2-0 at Ninian Park, defeated England 2-1 at Blackburn Rovers’ Ewood Park and completed the whitewash with a 1-0 victory over Ireland at Windsor Park in Belfast.

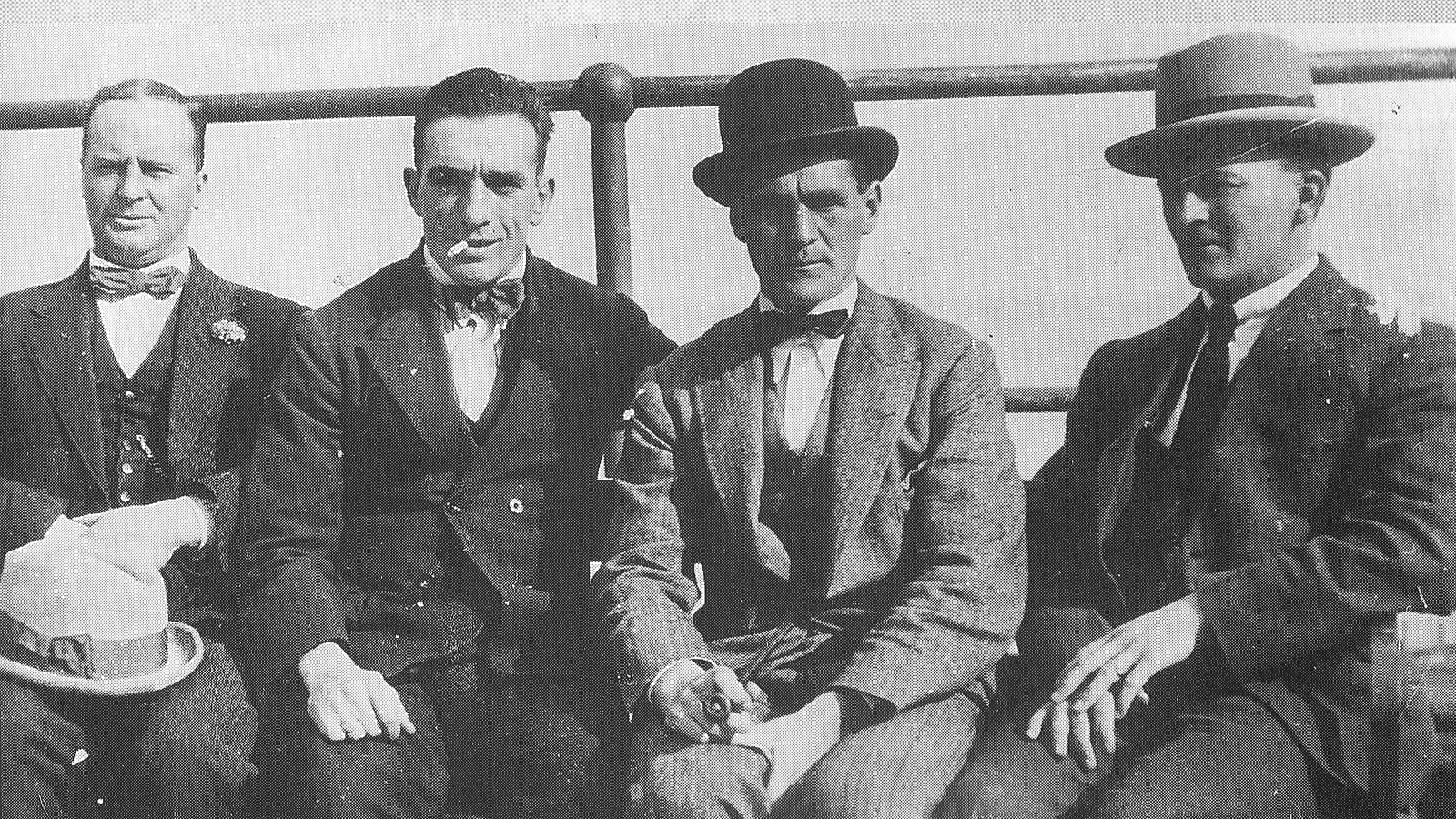

Herbert (second from the right) on a trip to Southport in 1923 alongside Cardiff City men, George Latham, Jimmy Gill, and Billy Hardy (left-right).

Blighted By Injury

Herbie made 93 Football League appearances for Cardiff City between 1920 and 1926, but his career as a Bluebird was blighted by a double fracture of his left leg in a 2-1 defeat away to Blackburn Rovers at Ewood Park in 1924 (in a cruelly ironic twist, the setting of one of his finest matches for Wales, against England, in the March of that year). This terrible injury would keep him out of action for two years. He eventually returned to the game and transferred to Tranmere Rovers alongside team-mate Alfie Hagan in 1926, where his quality immediately earned him the team’s captaincy. Sadly, after 44 League appearances for Tranmere, lightning struck for a second time: he broke his right leg and by 1928 his football career was over.

After football, Herbie continued to work in a clerical role, this time for the Post Office in Cardiff; in 1938 he married his sweetheart Phoebe Hewett from Llandaff North. They lived for a time in Cathedral Road but eventually settled in Dinas Powys where they resided until Herbie passed away at Llandough Hospital on November 19th, 1982, aged 88. Phoebe died two years later.

Herbie Evans was a man of contradiction.

As a soldier he narrowly survived a Turkish storm of steel in 1917, yet as a footballer it was ill-luck that caused him to suffer an injury which meant he missed out being part of the 1927 generation.

Herbie was a quiet local hero who should be remembered as one of the great Bluebirds of the 1920s.

To tell us your stories of war heroes past and present, email forever@cardiffcityfc.co.uk.

Article written by Danny Richards.